Tools for science: trusting the black box

Tools and black boxes

My job as an astronomer can be reduced to three main steps: 1) observing the sky, 2) extracting information from these observations, and 3) using this information to draw new conclusions on our Universe. While the latter may sound like the most exciting step of all, most of my time is actually spent doing the second step, namely data reduction and analysis, and I suspect the same is true for most of my fellow astronomers.

Nowadays, astronomical data are reduced and analyzed exclusively on computers, using a wide variety of tools. By tool, I mean a piece of software (be it a simple script of a large compiled program), accompanied optionally by its documentation and source code. These tools include instrument pipelines (which convert raw observations obtained by a telescope into usable images or spectra), softwares to detect and extract sources in images (Galfit, SExtractor, T-PHOT, …), and so many others. Generally speaking, what a tool does is to read some kind of input, process it, and write some other kind of output for you to use. Most tools can be used as black boxes: you do not need to know how the tools work internally to use them. All you need to know is how to “talk” to the tool: what type of input it needs, and how it will output the results of its processing.

Let us consider, for illustration, a very silly tool I wrote for this article. The tool is called blackbox-hypot. It reads a plain text file containing two numbers a and b on each line, and outputs in another plain text file the square root of the sum of a^2 and b^2, for each pair of numbers. You can get and compile the source code here. With the information I just gave you, you can run the program on all the values you want and obtain the most wanted root sum of squares. That’s what a tool is.

But is using the tool really all you need? All tools will tell you: “Give me X, and I will give you the corresponding Y”. As scientists, our first reflex should be to doubt. Is it really Y we are given? And if not, how far is the tool from actually giving us the true value of Y? The answer to this question is not always easy to obtain, even though it is obviously crucial.

Just from what I told you about blackbox-hypot above, do you know how accurate its result is? No, not at all. For all you know, the code could return the correct value only within a factor of two. Or a random number.

Scientific tools are very specialized, cutting edge softwares which are used at most by a thousand people, and most often only by no more than ten. Compared to softwares like the linux kernel or any word processor, they do not benefit from a large user base which can report bugs and problems. Therefore you cannot simply trust that they work, you have to verify it for yourself. How do you go about it?

Read the freakin’ manual

(only they usually don’t say freakin’)

In the ideal case, the author of the tool has written a detailed specification. It describes how the tool is supposed to behave, in some form of a contract: “if you give me a X which satisfies this list of criteria, then I can give you an estimate of Y with a precision of Z%”. This kind of statement is usually found in the documentation of the tool, and suggests that the author has actually performed tests to quantify the accuracy. That’s a good thing.

If I had written a documentation for blackbox-hypot, I could have written this: “if you provide a pair of any two finite numbers, the code will return the root sum of squares of these numbers with a relative accuracy of 5e-8”. That’s 0.000005%, not bad huh?

Break the box open: look at the code

Unfortunately, most of the time this information is not available in the documentation, if there is any documentation at all. See, I didn’t bother writing one for blackbox-hypot… Or perhaps the documentation became outdated after an update of the code. Now you could send an email to the author, and hope for a response within the year. Or you could look at the source code.

The code is, in principle, the ultimate documentation: contrary to a hand-written document in human language, code is not ambiguous, and it remains up to date by construction. It cannot lie about what the program does, because it is the program (truly a representation of it, but you get the idea). Simply reading the code can let you spot edge-cases and limitations, for example you can see that the code might perform a division by zero, or that the author used a hard-coded limit for this or that array, etc. Even better, if you understand the algorithm, you can prove mathematically that the code is doing the right thing (or not!).

Go on, take a look at the code of blackbox-hypot on github. You will see that the program computes sqrt(a*a + b*b): you don’t have to take my word for it, now you know it is doing the right thing.

The only downside is that people (and astronomers in particular, it would seem) tend not to care for the quality of their code very much. It is not unusual to encounter large pieces of code commented-out (who knows if this was intended or not?), obscure variable names, or terribly convoluted implementations. Or simply, you may not be familiar with whatever programming language in which the code was written (FORTAN?).

But clearly, the worst case is when the source code is not publicly available. This seems to be less and less common in astronomy, but there are still a few famous examples. The one I am most familiar with is Galfit, a tool commonly used to model the profile of galaxies. This program cannot be made open source because it uses pieces of code which are copyrighted (likely coming from Numerical Recipes, a famous book containing numerous algorithms for scientific analysis). How bad such copyrights are for science could be a topic for a another blog post. Fortunately, in the last decade a number of great on-line platforms were created for hosting and managing open source softwares, such as github which is entirely free. Unless you are doomed by these copyright issues (which is something you should avoid at all cost from the beginning), there is little excuse not to use these services, and I strongly recommend you do.

Reinvent the box: write your own software

If you cannot understand (or even read) the code, at this stage you have two options: either forget about the source code and go to the next section, or rewrite the software in ways (or in a language) you understand. If you have at least a vague idea of what an implementation is supposed to be doing, and if you have the programming skills, taking the time to rewrite the code from scratch can prove a very good time investment for you, and may save the trouble for others later on. It may not run as fast as the original at first, but what matters chiefly is that you control the code.

This is an approach I have followed on multiple occasions. Only after I got my version of the code working did I really understood what the original program was actually doing, and discovered its main limitations. Better, part of what I learned was not limited to this specific tool. Each time, I grasped new concepts that I could apply elsewhere: fast and generic algorithms, better software architecture, or even a clearer understanding of some of the math or physics. I do not regret all the hours spent getting it to work!

In the end you’ll have on your hands a code that is cleaner, and perhaps it also runs faster. If you make it public, the future users of your code may not have to go through this rewriting stage to understand it, and you will have done a great service to your community.

Illustrating this with blackbox-hypot may not be very enlightening, as there are not so many ways to implement this tool. But beyond the numerical computation itself, perhaps you are concerned that my tool is not reading values correctly from your input files? Input/output in standard C++ can be obscure, and perhaps you do not understand how I implemented this. In this case, go ahead and write your own version with your favorite language!

Control ins and outs: simulate datasets

Drawing conclusions on the tool based on its source code is called static analysis. We never had to run the tool so far to check anything, we just used logic. This approach can be very time efficient, but it ultimately relies on how smart (or awake) you are. We are all humans, and we cannot reasonably be expected to spot all the problems of a code simply by looking at it. That’s where dynamic testing comes to the rescue: we run the code and see if it works!

Usually we need the tool to solve a problem, the answer to which is unknown to us and cannot be trivially predicted; if we had a way to predict what the output of the tool would be, we wouldn’t need the tool in the first place, right? However, there may be some special cases where this prediction is actually trivial. Consider blackbox-hypot: we know that if we give it two zeros in input, it should output zero. Likewise, the square root sum of any number and zero should output this number untouched.

Alternatively, in many cases there exists a slower (“brute force”) method which solves the same problem as our tool; we do not want to use it for all our calculations because it is too slow, but we can use it to generate a few outputs, which we can use as a reference. If you have no way to predict what the exact output values should be, perhaps you know of some properties that these values must have? For example you may know that the output must be an odd number, or that if you double the values in input then the output should be doubled as well. Using this special knowledge, we can generate a suite of inputs for which we know in advance what the output should be (or how it should relate to the other outputs), and check that the tool does produce the expected result. This very direct approach can quickly reveal whether the tool behaves as advertised or not.

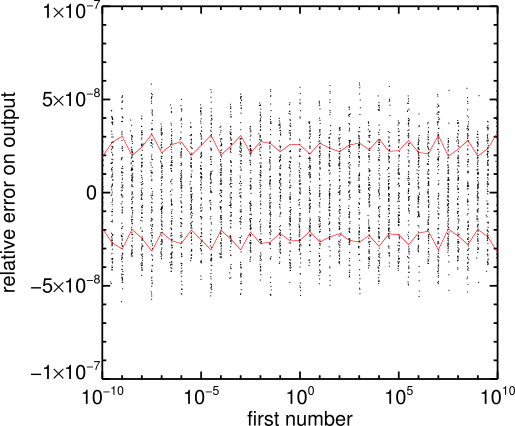

In the case of blackbox-hypot, we can do the computation by hand down to a precision of our choosing, or carefully perform the computation with a high precision floating point library. I used the latter (mpfr::real), because I simply cannot compute square roots on a piece of paper, and tried computing various root sum of squares of randomly generated numbers. Here is the relative error I found:

Black points show the measured difference between the output of blackbox-hypot and the true value computed with the high precision library, and the red lines show the 16th and 84th percentile, i.e., what we usually call the 1-sigma confidence interval. As advertised, the relative error is of the order of 5e-8, for any number between 1e-10 and 1e10. You are immediately reassured: it seems my documentation above was true.

Use all the help you can get

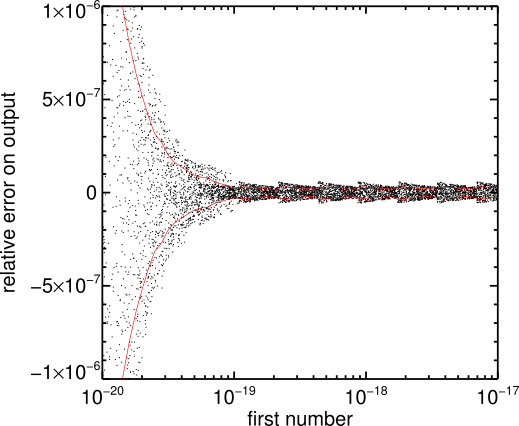

But that is not the end of the story. There is one problem with this method: to truly demonstrate that the tool works we would have to try every single possible combination of input numbers, and there are simply way too many. The test above has covered a lot of ground, but in fact you can see there are gaps: not all numbers were tested. It is reasonable to expect that, if the tool works for values of 1, 10 and 100, it should work for 20, 22, 35.125, pi, etc. But we don’t know for sure until we’ve tried. In fact, as you can see from the plot above, the errors are not truly random: they show some structure with some specific numbers having lower errors than others. Perhaps there are some numbers we haven’t tried yet which have a much higher error? Let’s see what happens when we re-run this test for much smaller values:

All of a sudden, all hell breaks loose: the relative uncertainty grows much larger than 5e-8 if the value becomes smaller than 1e-19. The origin of the issue is that the numbers are squared and summed: if the square of one number becomes smaller than 1e-38 (the smallest absolute value for a single precision float on my machine) we cross the limit of the numerical precision and the sum will not work as expected. In this case, the relative uncertainty climbs up by orders of magnitude, and can quickly reach unity (meaning: we are completely wrong). This highlights one important fact: the tests you perform must cover the range of values that you expect for your input data (with some margin, to be safe). If they don’t, you risk encountering a situation like this one, in which the tool behaves fine for most of the input values you can throw at it, but will fail miserably in a few cases you haven’t thought of.

Some of you may know it: there are of course better ways to implement this tool (using the std::hypot function, or higher precision floating point numbers), but that is not my point. My point is that, as a user, you will be confronted with tools like blackbox-hypot which do not have a perfect implementation, and you should know how to deal with this.

The only way to know how the tool works for any number would to go back to static analysis: read the source code to see which operation is performed, and study the specifications of the floating point format of your CPU to understand what is going on. It’s no fun, but it is doable. The point is: you shouldn’t limit yourself to just testing, or just reading the code. Neither solutions are perfect, but the best you can do is to use them both.

Conclusions

There is much more one could say about testing software. My point here was not to be exhaustive, but merely to show what options you have, as users of a tool, to make sure it does what you want.

My messages can be summarized as the following.

If you use scientific tools:

- Never use tools blindly.

- At least read the documentation and test basic situations.

- If you want to publish the output of a tool, take the time to understand what it does and that you control the output. Look at the code if you have to, and do exhaustive tests before submitting your work to a journal.

If you write scientific tools which are meant to be distributed to others:

- Release the source code.

- Take the time to write clear code, adding comments only where you cannot make the code clear enough to be understood on its own.

- Provide a documentation, and show some tests to prove your tool is working at least for the most basic inputs.

If you pay people to do science, please consider that writing good tools takes time, and that an hour spent in making a tool better is ten hours saved for its users (including the author!). Given how important computers have become in science, writing software is now a key aspect of the job of a scientist, and it should not be dismissed as “only a technical thing”. Scientific programming should be outsourced very carefully, and it certainly cannot be treated as fully separable task in a research work, since only by understanding a code can a user fully trust its output. The same is true of instrumental work, and this is the reason why we should keep sending astronomers to observe at a telescope, rather than systematically resorting to full-time telescope operators. But that’s another story.

Managing software will become a central problem in the “big data” era we are entering. To handle the huge amount of observations that the next generation instruments will provide, tools have to become increasingly complex, to the point that the majority of today’s scientists may ultimately not have the skill required to write or even understand these tools.

How to solve this issue and preserve good quality science is not clear to me. Part of the solution may be to require of softwares what scientists nowadays require of instruments, namely extremely rigorous specifications and testing, so that users can trust tools almost blindly. Large projects such as Euclid or LSST are going down this road, and the large size of their expected user base will surely contribute in building trust in these tools.

But smaller tools and codes will always exist, and nothing will ever truly save you, the user, from testing them!